Remembering The Next Web: 2006-2025

No, you're crying.

Note from Matt: This isn’t this week’s main post, but rather something I wanted to write for myself. It’s a bit different, and it’s personal. You may enjoy it, but I won’t be offended if you give this newsletter a miss.

I’ve got a premium post coming up next (ideally tomorrow — and yes, I know I said I was going to publish it on Monday. It’s… been a week) and a free one after that about generative AI and mental health. You’ll want to stick around for that!

Earlier this month, The Next Web (TNW) announced that it would shut down its media and events operations by the end of September, putting an end to perhaps the only European tech publication that rivalled those in the states.

This isn’t the kind of thing I usually write about. While so much of what I write about is rooted in nostalgia, it’s the kind of nostalgia that everyone can relate to. How social media used to be good, before it wasn’t, or how tech companies have completely destroyed the concept of ownership, turning their customers into digital serfs, with them assuming the role of feudal landlords.

This stuff is personal to me. As I wrote in the introductory post to this newsletter, I spent a lot of time working at TNW. It was the first salaried position I had in media, previously working exclusively as a freelancer.

I don’t think I’ll ever have another job like TNW, unless I make one for myself (which is, admittedly, kind of the point with this newsletter). It gave me near-complete creative freedom, from which I was able to explore the stories that mattered to me — and which, I hoped, would also resonate with the readers. It encouraged me to find my strengths and play to them, and to take risks that other publications simply would not tolerate.

Some of my best friends are those who I met with TNW, and we’ve remained close even after I left the publication in late 2019.

I met Ed Zitron, my kind-of boss, through TNW. A few years later, I ended up working for him. Ed gave me the courage to start my own thing. Literally, if it wasn’t for TNW, I wouldn’t be writing this newsletter right now — and you wouldn’t be reading it.

Sidenote: Therefore, if you take objection to anything I write in this newsletter going forward, make sure you CC him in all your hate mail.

Beyond that, TNW mattered because it wasn’t like any other tech publication. Although our audience was (as you’d expect) heavily dominated by Americans, we were very much European in our outlook and our editorial team.

When I was there, most people worked from the Amsterdam office (which also shared space with a startup incubator, and had the coolest rooftop bar looking over the canals). A few people worked remotely in the US, or India, or in the case of myself, the UK.

The fact that we weren’t based in New York or Silicon Valley was an asset — and was the main thing that separated us from the competition.

It allowed us to pursue stories that other publications wouldn’t consider, simply because they felt distant and unimportant to them.

When crypto was the hottest new thing, and the UK was figuring out how to disentangle itself from the European Union without causing a second civil war in the North of Ireland (canny readers will know where I stand on Irish unification from that particular bit of wording), the then-chancellor at the time suggested that blockchain technologies were an “obvious” solution. TNW gave me the freedom to write a feature-length op-ed explaining the complexity of the Irish land border, and why that suggestion was as moronic as it was insane.

TNW gave me the freedom to go to Salt Lake City and explore why, despite only accounting for around 60% of the population of Utah, former Mormon missionaries account for the majority of tech founders in Silicon Slopes.

Sidenote: The answer is kind-of interesting! Mormon missionaries are selling the hardest thing to sell — not just a religion, but a value system and an understanding of metaphysics — and they’re doing it often in a language that isn’t their native tongue. They’re dealing with rejection every day. This gives them a set of soft-skills and resiliency that’s really useful in entrepreneurship.

Because TNW wasn’t trapped in the Silicon Valley bubble, I got a chance to cover promising (and interesting) startups that otherwise wouldn’t get a glance from the American press, in part because they weren’t located in that precise geographical bubble.

Our distance from the Californian heartlands of the tech media allowed us to be adversarial with the companies we covered. I wrote an op-ed arguing for a boycott of Amazon over its labor and tax practices — something that I doubt would fly anywhere else, where access is something to be protected at the cost of one’s credibility and conscience.

The other thing that separated us from our American peers was that we didn’t take ourselves too seriously.

When Alejandro Tauber (who inspired this piece published a couple of weeks ago) assumed the role as managing editor, he decided to give the site a new visual identity defined by quirky, out-of-the-box featured images on the top of every article.

I’ve always hated art and design (to be clear, doing art and design). As I’ve written previously, I have a condition called dyspraxia — also known as developmental coordination disorder — which makes it hard for me to actually create something that looks visually impressive.

Words, I can do. Pictures? Nah mate.

Tauber insisted that every writer get onboard with his new vision for the site — myself included. This resulted in what I can only describe as an act of malicious compliance from myself, where, in a story about California’s regulation of drone-delivered cannabis, I fired up Pinta and created this work of art.

Yes, that is a stock picture of a delivery drone with “420” sprayed on it. What’s even more remarkable is that this was actually published.

Another time, a random dude tried to bribe me $10 to publish a guest post under my byline advertising a dodgy crypto company. Yes, ten whole dollars.

Normally, I’d play along, asking the guy offering the bribe to pay me an insane amount of money in a very specific shitcoin (“$10,000 in JesusToken, final offer”). This time around, however, the guy sent me the draft of the article in the opening message. And the article was configured to allow anyone with the link to edit it.

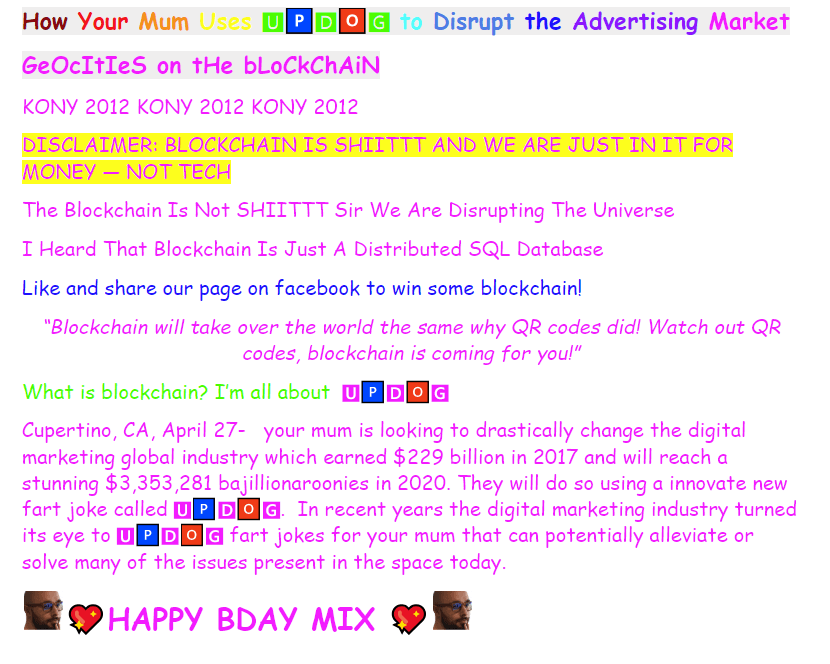

I posted it to Twitter. Ed (and a few others) retweeted it, and suddenly there were dozens of people giving this spammy article an unsolicited makeover. Quoting myself:

People have always said I take jokes too far. If there’s a line in the sand marked “too far,” I regularly speed past it like Lewis Hamilton in the Monaco Grand Prix, until it’s just a faint shadow in the rear-view mirror. Take, for example, the unfortunate KFoodRecipes.

KFoodRecipes (presumably not his real name) tried to get a really spammy promotional guest post published on TNW. The post was about one of the many nebulous blockchain companies that have sprung up of late, called Ubex. It was bad.

He was persistent, and he even tried to bribe anyone who would respond to his tweets with the insultingly low-ball amount of $10. Obviously, we had fun with him.

I strung him along and tried to get him to say “what’s updog,” because I’m a five-year-old cunningly disguised as a 26-year-old.

(An unoriginal one at that, as this is a joke PR maven Ed Zitron has been pulling for years, but as Wilde purportedly once said “talent borrows, genius steals,” ¯\_(ツ)_/¯)

But then my afternoon took an amusing turn when UK-based publicist Rich Leigh spotted that KFoodRecipes had left the document publicly editable. Then the fun really began.

We couldn’t help ourselves. Suddenly every reference to “blockchain” was replaced with “updog.”

Then “Ubex” became “your mum.”

And then the trolling picked up momentum, and random strangers started turning this dreadful blog post into something that wouldn’t have looked out of place on GeoCities circa-1999. I’m talking about retro GIFs, all-pink text, and the generous use of comic sans. Someone even copied in the entire lyrics to The Fresh Prince of Bel Air.

I could go on, but as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

I basically wasted an entire afternoon trolling a guy who tried to bend my journalistic integrity with the power of an Alexander Hamilton — but it was totally fine, because I got a good story out of it.

That was TNW. We didn’t just take the piss out of others — we took the piss out of ourselves, as well. We weren’t afraid to be earnest, or to point out our own failings, or to laugh at our own shortcomings. We knew that while there were times to be serious, there were even more times that called for joviality.

There isn’t much money in media, but there is in conferences — especially when you’re charging hundreds of dollars for a ticket. That’s part of what kept the lights on at TNW. The media side acted as a kind-of loss leader for the events business, where tens of thousands of people would converge on Amsterdam for a few days of mingling, drinking, and watching talks from shiny-haired Californians.

This would be an opportunity for the team to convene, and for new members of the team, it would be perhaps the first time they met their co-workers in the flesh. And it was a testament to the camaraderie we shared that we all got along, with no drama, lots of hugs, and some sad farewells at the end of the event.

That’s not to say that things weren’t occasionally chaotic. There were times I’d be staggering around the grounds of the cavernous Westergasfabriek and its surrounding park, hungover as sin, and I’d get a text from my boss saying that I needed to do an on-stage or on-screen interview with a founder in the next ten minutes. I’d then have to bullshit my way through talking about something that I’d never even considered before, like the sneakerhead fandom or competitive drone racing.

Part of the reason why I’m so nostalgic for my time at TNW is that I grew as a person so much while I was there. It forced me to learn to think on my feet, and to become an even better bullshitter than I already was.

Another fond memory of my time at TNW involved myself and a Scottish PR friend bumping into a guy who looked remarkably similar to Moby — insofar as he was bald and wore glasses. For the next couple of days, whenever I saw him, I’d insist that he was, in fact, the creator of Porcelain, and not actually a Bulgarian software developer on a business trip.

By the end of the event, multiple people were in on the joke. Anyway, here’s a picture of me with “Moby.”

Over its nearly two-decades of existence, TNW went through a whole bunch of incarnations — from a blog, to a site focusing on startups, to one that focused on tech culture, to one that tried to resemble the journalism on Vice and Motherboard, before returning again to covering primarily startups.

It’s a journey, and one that I was privileged enough to be a part of, even if only for a short amount of time.

And while I’ve talked a lot about the stuff I did personally, I also want to stress that my colleagues did some amazing shit, and I’d be the biggest asshole imaginable if I didn’t finish this post without mentioning some of their work.

Bryan Clark’s investigation into a shady diamond company, which offered “conflict-free gems” but couldn’t actually verify whether said diamonds came from Canada or were mined by toddlers in Sierra Leone, was incredible, time-consuming work that involved him taking on some personal risk.

Bryan was also an incredible editor who didn’t tolerate sloppiness, and always pushed me to be better.

Napier Lopez taught me how to review phones, and his write-up of the Galaxy Note 7 was an absolute masterclass — even if he did have to temper his initial enthusiasm with a note a few weeks later saying, in short, “don’t buy this phone, it’ll set your house on fire.”

Nino DeVries was one of the best social media guys in the game, even if I still haven’t quite forgiven him for changing the headline to one of my articles without asking, and for changing my emoji on the company slack to Post Malone. (Yes, when I had hair, I did bear a striking resemblance to Mr Malone, save for the face tattoos).

Abhimaniyu Ghoshal was one of the kindest, most incisive editors I’ve ever worked with, and I’d make a point to start work early so that my shift overlapped with his workday in India. He’s one of the best in the business, and he’s a beautiful human being.

Georgina Ustik brought light into the office, and despite being American (albeit with an English mother), she could go toe-to-toe with the Brits when it came to workplace banter.

Callum Booth is, and was, a delight, and his post-TNW work on The Rectangle is worth a follow, if you haven’t already.

Már Masson Mack made me feel useful, and always asked for my input when reviewing a guest post that touched on my background as a software engineer — even if I did make fun of his baby-faced features by calling him the Milkybar Kid, which culminated in Nino photoshopping Már into a Milkybar advert, with “Milkybar” replaced with “Milkymár.”

Lauren Gilmore was another editor who demanded the best from me, and her unforgiving scrutiny of my copy made me a better writer. She also gave the best hugs at TNW — although Yessi Bello Perez, who joined before I left, came a close second.

Tristan Greene was, and still is, an incredible science writer.

Boris Veldhuijzen Van Zanten, who founded TNW, was the guy who gave me a chance, and on my first time in Amsterdam to meet the team, he invited me and my wife into his home for dinner. Another genuinely beautiful human being.

I could go on, and on, and on. Mix. Ailsa. Juan. Guðrun. Anouk. Camille. Ashley. Pablo. Carissa. Inés. Martijn. Matthew Elworthy. Merilin. Nat. Robert and Patrick. Wytze. Simon. Robin. Yoni. Esther. Sebastien. Laura.

I’ve probably missed out a few names there. Forgive me if you weren’t included (and if you’re mortally offended, you can always drop me an email and I’ll update this post). There were so many people I worked with that were so good, and so smart, and so kind, and I’m devastated that there’ll never be another TNW.

I left TNW a few months after the Financial Times took an initial stake in the business. Over time, the FT’s share of TNW grew.

I don’t know the circumstances that led to TNW’s end. Media is — especially ad-supported digital media — is a notoriously unforgiving business. Covid, which killed the events side for a couple of years, likely didn’t help either.

Either way, it’s a sad end for something that feels so irreplaceable — a European tech media institution that didn’t aspire to be yet-another Techcrunch or The Verge, but felt comfortable in its home continent, and at times, being deeply idiosyncratic and weird.

There’ll never be another TNW. Long live TNW.

Oh boy, nothing but great memories. The times we had….

Aw Hughes!! ❤️❤️ we’ll never have a team like that again 😭