How The Internet Died

Dissecting a tragedy of the commons

Note from Matt: Yeah, this newsletter is more than 10,000 words. It’s — in the language of my people — an absolute unit. As a result, you won’t be able to read this in your inbox. You’ll have to click through and open it in your browser, or through the Substack app.

In 2021 — more than one year before the release of ChatGPT — a user on the online forum AgoraRoad called IlluminatiPirate described the “dead internet theory,” which claimed that since 2016, the majority of online activity has been driven by bots operated by shadowy actors with a desire to shape public opinion.

IlluminatiPirate writes how, around 2016, he noticed a drop in the production of user-generated content:

“The Internet feels empty and devoid of people. It is also devoid of content. Compared to the Internet of say 2007 (and beyond) the Internet of today is entirely sterile. There is nowhere to go and nothing to do, see, read or experience anymore… Yes, the Internet may seem gigantic, but it's like a hot air balloon with nothing inside.”

Around the same time, he noticed a spike in inauthentic content on 4Chan, which he suspected was created by a bot:

“Roughly in 2016 or early 2017 4chan was filled with posts by someone or something. It wasn't spam. The conversations with it were in real time, across multiple boards and multiple threads simultaneously. Its English was grammatically correct but odd (I'm not a native English speaker and am thus sensitive to its misuse), similar to how a Japanese person may use it. A sense of childlike curiosity and a childlike intellect emanated from these posts. It posed a LOT of questions, usually as if trying to understand the emotions of the posters it was talking to, as if unfamiliar with human emotions. Communicating with this "poster" was an odd experience, I could sense something was off but not malicious. I am absolutely certain this was an AI of some sorts. This "poster" was active only for about a week, and as far as I know nobody has ever mentioned or noticed this Anon.”

Beyond the web, he also observes that popular culture has, similarly, become staid and unremarkable.

“Algorithm fiction. Do you like capeshit, Anon? How about other Hollywood stuff? Music perhaps? Have you noticed how sterile fiction has become? How it caters to the lowest common denominator and follows the same template over and over again? How music is just autotunes and basic blandness? The writer's strike never ended. Algorithms and computer programs are manufacturing modern fiction. No human being is behind these things. This is why anime looms so large - even a simple moe anime has heart because there's actual people behind it, and we all intuitively feel this.”

I’ve linked the entire post above. As a thesis, it’s unambiguously conspiratorial. IlluminatiPirate raises the prospect of convincing deepfakes holding key positions in popular culture, and possibly politics. He believes that the trends he’s observed point to one inevitable conclusion:

“There is a large-scale, deliberate effort to manipulate culture and discourse online and in wider culture by utilising a system of bots and paid employees whose job it is to produce content and respond to content online in order to further the agenda of those they are employed by.”

He then goes on to list those he believes are responsible, with Facebook and Twitter blamed, as well as the CIA and a CIA-owned venture capital firm. Like any good conspiracy theory, it blends observable reality (the Internet really does feel inauthentic) with wild assumptions, and it stitches together real phenomena with an overarching nemesis that’s singularly responsible for all of them.

The Internet is full of conspiracy theories. And yet, the Dead Internet Theory stands out insofar as it’s received coverage from major, well-respected publications like The Atlantic, the BBC, and Prospect Magazine who have, for the most part, given it a fair hearing, skimming over the nuttier parts while acknowledging the paradigm shift we’ve seen on the Web over the past decade, especially as it comes to user-generated content.

The Atlantic’s search headline is a great example of this: “The 'Dead-Internet Theory' Is Wrong but Feels True”

Another factor behind the rise of the Dead Internet Theory is that, like any non-scientific theory, people can change the meaning to reflect the things that they observe, and to discount the things they disagree with, and to add new stuff to bolster their arguments.

And yes, the Internet does feel dead — especially compared to what we once enjoyed — and the emergence of things like generative AI has only compounded that feeling of dead-ness.

In this newsletter, I want to put forward a more systematic Dead Internet Theory — albeit one that, I freely admit, is based on my own subjective definition of the Internet and my interpretation of the factors that led to its demise.

I’m writing this because I feel that by understanding what we lost — and how we lost it — we can, perhaps, find ways to reverse the decline. Or, at the very least, identify the real figures who are responsible for this historical tragedy of the commons.

What do we mean by the Internet?

If we want to write a coherent “theory of the dead internet,” the obvious first step is to define what we actually mean by “the Internet.” It’s a tough question, in part because over time, the Internet’s definition has changed.

Are we talking about the basic protocols that power the Web? Is the Internet the TCP/IP model that every CompSci student learns about in an introductory networking class? Do we focus on centralized platforms and user-generated content (as IlluminatiPirate did), or do we take a more holistic look that examines the health of the Web beyond a handful of sites like YouTube, Facebook, and Google?

Side note: Earlier this week, I was out for coffee with a friend and we were talking about this newsletter, and he said “are you talking about the death of the Internet, or the web?”

By that, he’s distinguishing the Internet (the various protocols and connections) from the web (which is the stuff we do in our browser). No doubt to the annoyance of many of my more technical readers, I’m going to be using both terms interchangeably.

Or is there something ephemeral about the Internet — something that makes this conversation all the more important, but simultaneously, makes the thing we’re talking about harder to define? Is the Internet more than the sum of its parts? More than the protocols, and the websites, and the user-generated content, just like a person is more than their heart and their lungs?

These are tough questions, and I recognize that they’re inherently subjective. Your answer will, I imagine, change based on the things that you value, the things that you do online, and (perhaps) your age. I’d imagine — though with no degree of certainty — that those who entered the online world in the 1990s, before its mass-commercialization, will probably put less emphasis on those centralized platforms mentioned earlier, especially when compared to someone who grew up with them.

I thought about this for a while. Part of the reason why this article has taken so long to write is because finding that definition has been so incredibly hard. I ultimately came up with the following points. This is my platonic ideal form of the Internet:

Equality of information: This point isn't absolute (and I recognize that there will always be regional variations here), but a healthy internet should allow people to access the same information on the same terms, no matter where they live.

Equality of experience: Again, this isn’t absolute, but a healthy internet should strive to give people the same experience irrespective of where they live.

Decentralization: For the Internet to function properly, it shouldn’t rely on the involvement of corporate players, and where those commercial interactions exist, they should be interchangeable, and arguably optional. The precursor to the Internet, ARPANET, was designed by the US military to be able to withstand nuclear warfare, in part because it wasn’t centralized. The Internet of today should reflect this.

A living historical record: To a certain extent — and you can debate how much — the Internet should act as a historical record of humanity. That means allowing for content preservation, but also implies that third-party actors can’t just eliminate huge swaths of information on a whim.

User-driven and driven by user-utility: The last point is obvious. The web is the product of the stuff that people do with it. As a result, any changes — whether the underlying technologies of the Internet, or the platforms that people use — should reflect that and help people do the stuff that they want to do.

There you have it. I recognize, again, that this is hugely subjective — and I fully expect to get comments from people that fundamentally disagree with the points above, or would choose to expand it with their own ideas.

Ultimately, these ideas boil down to the idea that the Internet shouldn’t be under the control of one person — or one company — and that it should be a place for people to do stuff. Whether the Internet is dead or alive (or moribund) depends on how well it meets these standards.

The Splinternet

As a writer, I’m constantly researching stuff. For every story I write — whether that be a piece of journalistic writing, an article I ghost-write for a client, or a newsletter I write for myself — I read through hundreds of pages of documents, news articles, and so on. The more I write, the more I read.

Over the past few years, the research part of my job has gotten much, much harder, and a major reason why is because I live in the UK. Despite having left the European Union in January, 2020, we still retain the same GDPR-based privacy legislation that establishes requirements for how sites collect and process user data, and imposes severe penalties for noncompliance.

To be clear, I think GDPR is a good thing. However, I also recognize that many businesses have simply decided to stop servicing European users rather than take the effort to ensure their online presence is compliant. The biggest — and most annoying — example, in my experience, is local news websites in the US.

Side note: I’m going to be talking about a lot of UK/EU specific things here. While this isn’t relevant to Americans specifically, I’d argue that if you care about the Internet being a coherent, global space, it matters to you.

Similarly, if you care about people outside America being able to understand America through its hard-working, underpaid, and precariously-employed local journalists, what I’m about to say matters.

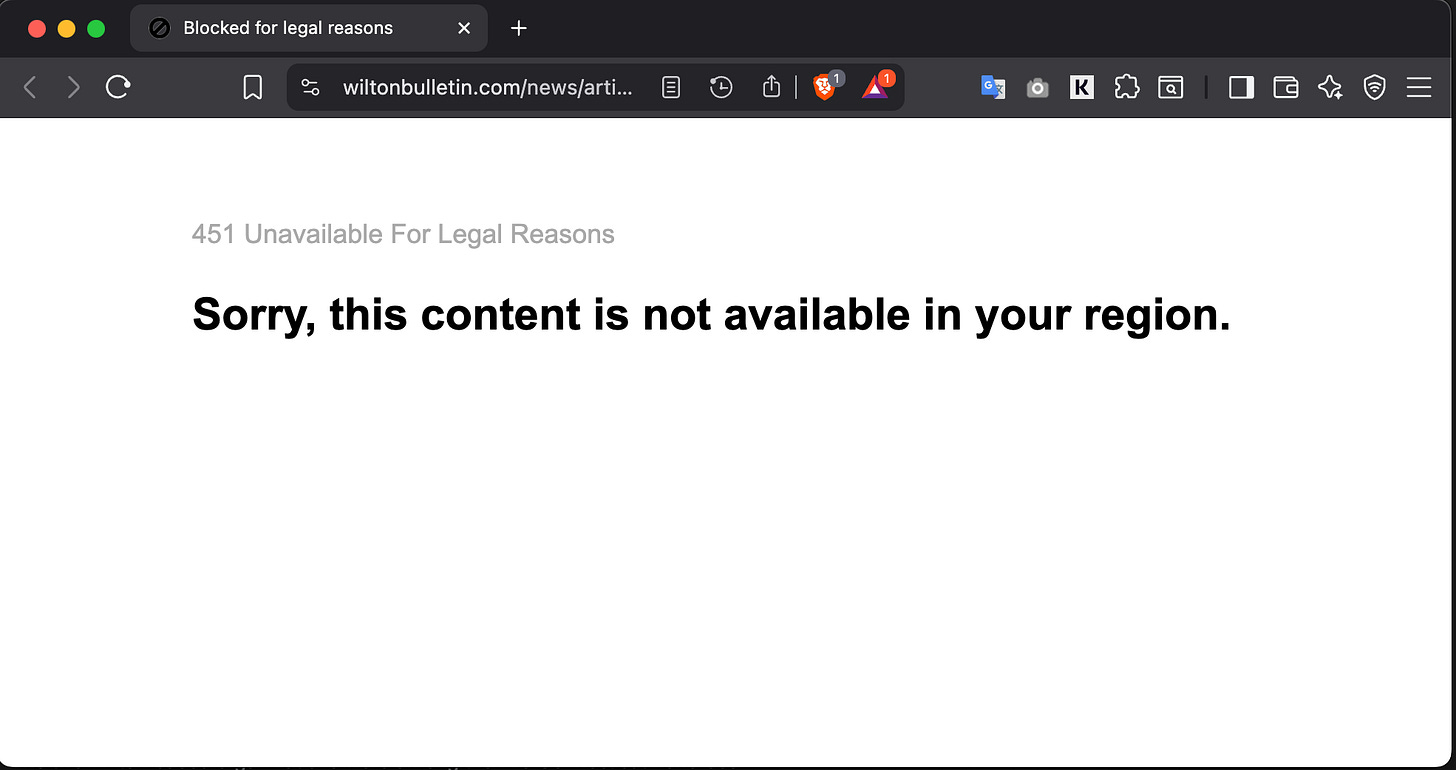

Most Americans don’t realize this, but if you open a small-time US news site (by that, I mean one serving a specific geographical region, and not a larger national blog or newspaper) in Europe, there’s a 50/50 chance that you’ll be presented with something like this:

In some areas, where the decimation of the media has meant that there’s only one publication serving a city or a county, it’s literally impossible to access a local news site from Europe without first turning on Tor or loading up a VPN.

While this may sound like a small annoyance, and one that likely only impacts a small number of people — like the handful of Europeans who care about the happenings in Wilton, Connecticut — it does reflect the fact that the platonic ideal of an Internet that provides an equality of information.

You might counter that what I’m describing is, in fact, the norm in countries where Internet censorship is routine, particularly when it comes to news outlets and sites that facilitate the creation and distribution of user-generated content (primarily social media websites, but also things like YouTube). And you’re right.

The experience of being online — and of accessing information — varies depending on where you live. Someone in China or Iran will have a completely different experience to someone in, say, the United States, or any other liberal democracy. This phenomenon even has a name: the splinternet, which was coined in 2001 by the Cato Institute.

But I’d counter by saying that such censorship was primarily limited to top-down decisions made in authoritarian regimes, where the control of information is essential to the survival of the government. This splintering was caused by commercial decisions (namely: that the cost of GDPR compliance is greater than any revenue that European visitors might bring in) in response to a piece of well-meaning legislation.

Similarly, we’ve seen a fragmenting of the experience of what it means to be online in ways that go beyond censorship or self-censorship, or the barriers introduced by online content providers in response to international privacy legislation.

In 2023, the Trudeau government in Canada launched the Online News Act, which required large social media platforms to compensate publishers for the content they syndicate. This bill was inspired by Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code, which entered into force in 2021.

In Australia, Meta initially decided to block all news content on Facebook — although it later came to a negotiated agreement with publishers, thus allowing users to share links from news websites to their network. This deal — as well as the deal struck by Google — is unlikely to be renewed in the wake of a tech-friendly Trump Administration.

In Canada, however, Meta stuck to its guns. It blocked news traffic and never reached a negotiated settlement, either with the publishers or the government. As a result, it’s now impossible to share news content on Facebook or Instagram.

Again, this is a small thing, but it’s emblematic of how the core experience of being online is different depending on where you live.

Which brings me to the complicated subject of the UK’s Online Safety Act.

Centralization

The UK’s Online Safety act, in a nutshell, requires online platforms to verify the ages of those who want to access content pertaining to certain sensitive topics, as well as explicit material. These categories are as follows:

Pornography

content that encourages, promotes, or provides instructions for either:

Self-harm

eating disorders or suicide

Bullying, abusive or hateful content

content which depicts or encourages serious violence or injury

content which encourages dangerous stunts and challenges; and

content which encourages the ingestion, inhalation or exposure to harmful substances.

While you might question whether placing the onus on platforms to protect children from this content, rather than, say, the parents, we can at least agree the sentiments underpinning this bill are reasonable.

Nobody wants to see kids bullied, or exposed to content that may exacerbate any underlying mental health issues (like pro-anorexia posts on social media). We can also recognize that while consenting adults can make informed choices about whether to consume pornography, there are serious questions about whether porn has deleterious effects on younger audiences — especially in the absence of decent sex and relationship education at school.

According to one US study — albeit one with a relatively small sample — a quarter of respondents said they learned about sex primarily through pornography. Another study suggests that pornography consumption correlates with sexual dysfunction in adolescents.

The reason why I’m doing this obligatory throat-clearing is to make it clear that my criticisms of the Online Safety Act aren’t, in fact, a dismissal of the idea that the Internet can be an unpleasant, unsafe, and even harmful place for children. But, rather, that the measures undertaken by the Online Safety Act are fundamentally opposed to any definition of the Internet that emphasizes equality of information, equality of experience, and decentralization.

Since the Online Safety Act went live, British Internet users have found themselves confronted with road-blocks to accessing online content — even that which, for the most part, doesn’t inherently conform with any of the above listed categories.

Want to send a DM on Bluesky? You’d best verify your age. Reddit, presumably out of an abundance of caution, has begun age-gating content about the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. On Twitter (as mentioned in previous newsletters, I refuse to call it X), a speech in parliament by MP Katie Weald was censored, as it “[contained] a graphic description of the rape of a minor by a grooming gang.”

This speech, I add, was broadcast live on BBC Parliament, and can be viewed online without any restrictions on Parliament's official streaming website, ParliamentLive.

It’s not merely that the Online Safety Act changes the scope of what information people can access, and how that access works, solely for users in the United Kingdom. The bill fundamentally forces online platforms to behave differently to British users, acting with an abundance of caution that otherwise isn’t required anywhere else. That’s why, for example, Bluesky requires that users be eighteen to read their DMs, or Reddit insists that users scan their face or verify their credit card to read details about the Ukraine war.

The Online Safety Act also transforms the underlying architecture of the Web, at least for Brits, installing mandatory gatekeepers. These gatekeepers are a handful of age-verification companies like Yoti and 1Account, and to use the Web now requires that you engage with them in a way that wasn’t previously required.

Side note: I just want to pre-empt something. I know I said a “handful of age-verification companies” in the paragraph above. There is — at least, at the time of writing — a decent amount of competition. I’m also cynical enough to know that said competition won’t last, and it’s only a matter of time that we’ll see some consolidation.

I’m not basing this assertion on anything concrete, other than the fact that this is how the tech industry usually works. You start off with a decent amount of diversity, and eventually, the larger companies grow their market share either through attrition (wearing out those at the back of the pack), or by buying their smaller competitors and integrating them into their business.I think it’s only a matter of time until age verification becomes a duopoly, or a triopoly. And, despite the assurances of the government that user data will be held securely, I can’t stress what a potential privacy nightmare that will be. It just takes one data breach for careers, marriages, and jobs to be ruined. Imagine the Ashley Madison scandal mixed with the Troll Trace story arc from South Park, and you’re just about getting there.

The modern web has always been, to an extent, centralized, with a handful of large hyperscalers (Amazon, Microsoft, and Google) providing the underlying hosting infrastructure of the Internet. To use the web means, inevitably, engaging with them. It means interacting with companies like Cloudflare, which handles things like content delivery and DDoS Protection. If you buy something, you’re likely providing your credit card details to a company like Square or Stripe.

This feels different, however. We’re talking about a centralization that isn’t optional, and that fundamentally affects the way the Web works.

If AWS went out of business tomorrow, its customers would just move to another cloud provider, and life would go on. Those customers could even decide to self-host their website or their application, buying a static IP from their ISP and an old computer that you install Kubernetes on. There’s no law that states you have to use AWS, or Cloudflare, or Ping Identity, or Okta, or Redis, or MongoDB, or any of the other big infrastructure providers that power much of the web.

Conversely, the web as we’ve long understood it now requires that these companies play a role in the interactions between users and the content they wish to see.

While we can argue about the intentions, the implementation of the Online Safety Act has been a catastrophe — and one the government shows no inclination of wanting to walk back, despite (at the time of writing) 519,137 signing a petition calling for its repeal.

From what I’ve been able to glean, the UK government dismissed any concerns about this centralization. Heather Burns, a British tech policy expert who consulted with the government during the formulation of the bill, was reportedly called a “paedo” for expressing her concerns about the bill, which ranged from the broad scope of content that would require age-gating, to the fact that the bill smacked of rent-seeking from the age verification industry.

From an interview with Scottish newspaper The National:

“I was actually in a meeting with the [UK Government in 2020] where I was called a paedo for trying to point out these issues to them,” Burns said.

“You go back to the office and talk about it and everyone gives you a round of applause and says, ‘You're in the club now. You're not up in the club until you've been called a paedo’.

Talking about the centralization aspect of this bill, she said:

Having been involved with the act since 2019, Burns described its drafting as “classic rent seeking – a policy term meaning when the lobbyists basically get to draft a law in their own interests”.

“The OSA has basically been legislated in this way in order to create a business model for age verification providers,” she added. “People don't understand that.

“The other thing they don't understand – although they may be starting to figure this out – is that if you're age verifying children, you're age verifying everyone. All of us are going to have to start giving our identification to any one of these providers, some of whom don't have great cybersecurity practices.”

She cited the ongoing Tea App scandal, where images, IDs, and messages of thousands of women were leaked, despite promises that the data had been deleted.

“There's now a layer in between [you and the website you’re looking at] provided by a third party, and we're just supposed to trust them,” Burns said.

I’m not an optimistic person — you should know this by now — and I fear that the UK’s Online Safety Bill will act as a roadmap for other countries, just like how Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code inspired Canada’s Online News Act. In doing so, it’ll check off three of the items on my list: An end to the equality of information and the equality of access that the internet once represented, and a mandatory centralization of the Web around a handful of small players.

Historical Rot

When I started writing this article, and had to come up with a definition for a healthy internet, one of the problems I identified was that every criteria I came up with was, to an extent, relative.

It’s impossible to have absolute equality of information or access on the Web, in part because licensing restrictions exist — which is why Netflix has different libraries for every country it’s present in. It’s why there are geo-restrictions on certain websites. Someone might, for example, block traffic from one country where their service or product is illegal, or where they see a majority of malicious activity coming from.

Similarly, my point about a healthy web being centralized has to be understood with the caveat that centralization is, to an extent, inevitable, simply because that’s how economies of scale work. If we’re talking about unit costs and margins, the larger companies — the likes of AWS and Microsoft Azure — will always have an advantage over a tiny hosting company that’s leasing a few racks in a data center.

That’s why I defined centralization as being something that’s imposed by an outside force, and that fundamentally alters the relationship that people have with the content they consume, and the sites they visit.

And so, when I talk about the Internet being a living historical record of the past, I need you to understand that I’m talking about this in relative terms. As a living entity, we’re going to see sites emerge and disappear. Link rot is a fact of life, and has been since the very beginning.

At the same time, a healthy Internet should allow for the preservation of the historical record without an outside force having a veto on said preservation, or being able to impose barriers or restrictions, or being able to destroy said historical record.

But that’s what we have. And I’d argue that this modern-day burning of the Libraries of Baghdad is a consequence of our reliance on a handful of growth-oriented private companies for our digital interactions, and the commercial incentives that stand in contrast to the need to preserve our online past.

I’m going to talk about three products: Reddit, Facebook, and Instagram.

Earlier this week, Reddit announced that the Internet Archive — a non-profit that has existed to create a record of the Web spanning back to 1996 — would no longer be able to capture Reddit pages, in part because generative AI companies were using this record for their training data.

As Reddit spokesperson Tim Rathschmidt told The Verge:

”Internet Archive provides a service to the open web, but we’ve been made aware of instances where AI companies violate platform policies, including ours, and scrape data from the Wayback Machine.”

Until the Internet Archive can provide assurances that these AI companies are prevented from accessing saved Reddit content, it will be limited to only preserving the site’s homepage — not individual posts or comments.

The abuse of the Internet Archive is a problem for Reddit, as its deals with generative AI companies account for a decent chunk of its revenue. It has arrangements with both Google and OpenAI, with the former reportedly bringing in $60m of annual revenue. Reddit also reportedly has another deal with an unnamed AI training data company, also said to be worth $60m.

And so, to keep this cash cow alive, Reddit is prepared to prevent the Web’s biggest historical record from accessing what, to many, is the front page of the Internet — a title it claimed from Digg.

Facebook, similarly, made another catastrophic decision this year with respect to the preservation of user-generated content, announcing that that live videos would no longer be saved in perpetuity, but rather automatically-delete after 30 days. Live videos uploaded before this announcement would also be removed, although users would have a longer timeframe (although the exact length was never explicitly stated) to either convert their videos to Reels, or to download them.

I’ll be honest — the way this announcement was covered by the tech media irritated me. Facebook, as one of the most valuable companies in the world (and one that’s highly profitable) can undoubtedly shoulder the (likely miniscule) cost of keeping these videos online. I imagine the data and bandwidth said videos require are a rounding error compared to the tens of billions it’s spending each quarter on the construction of data centers for generative AI services.

The majority of the coverage just simply repeated the points made in the press release — and didn’t ask any questions about the morality of, quite literally, deleting people’s cherished memories at a whim. Or, for that matter, asked “why.”

They didn’t push back on the assertion made by Facebook that this move would allow it to “align our storage policies with industry standards” — which is factually untrue, with both YouTube and Instagram saving live videos indefinitely. Nor did they ask how deleting millions of videos would allow Facebook to “ensure we are providing the most up-to-date live video experiences for everyone on Facebook,” or even what that even means.

Facebook said that “most live video views occur within the first few weeks of broadcasting” — but nobody asked the obvious question, like how that’s any different from any other content published to Facebook, or any other social media platform?

My gripes with the tech media world aside — the embarrassingly lazy, deferential, and servile tech media world — this is an example of a company deleting user-generated content over a near-decade-long period with (in my opinion) an unsatisfactory level of notice, and for reasons that are hard to understand.

Let me be clear: A healthy Internet wouldn’t allow this to happen. A healthy Internet doesn’t allow for one company to delete a decade’s worth of videos from three-billion users at a whim. That’s an insane amount of power.

And, let me be clear, these videos are history. Not all history is of national, or even regional importance. The grainy cellphone clip of your nephew’s christening, or the first dance at your wedding — they’re all stuff that’s of value, even if the only person who values it is you. It’s the kind of thing that, at one point, would have been captured on Super-8 film and put in a box in the attack.

Facebook, for better or worse, is the modern-day photo album. Nobody, and especially nobody as vulgar and hideous as Mark Zuckerberg, should be able to take that away from you. The fact that he can — and the fact that the tech media just shrugged this off — infuriates me more than words alone can convey.

Finally, Instagram. A lot of the points I’m going to mention in the next bit are repeated in my earlier newsletter, Losing Control, and it’s worth having a look if you’re curious.

Suffice to say, Instagram has done a lot to destroy its value as a historical record of the Internet, and again, it’s something that has received scant, if any, attention from the tech media — and certainly not in the full-throated tones that I’d expect from an institution that, in theory, should act as a watchdog against the excesses of the technology industry.

Allow me to confess something that will, for many of the readers of this newsletter, make me seem immediately uncool. I like hashtags.

I like hashtags because they act as an informal taxonomy of the Internet, making it easier to aggregate and identify content pertaining to specific moments or themes. In a world where billions of people are posting and uploading, hashtags act as a useful tool for researchers and journalists alike. And that’s without mentioning the other non-media uses of hashtags — like events, activism, or simply as a tool for small businesses to reach out to potential customers.

You see where this is going. A few years ago, Instagram killed the hashtag by preventing users from sorting them by date. In its place, Instagram would show an algorithmically-curated selection of posts that weren’t rooted in any given moment in time. It might put a post from 2017 next to one from the previous day.

What happens if you just scroll through and try to look at every post with the hashtag, hoping to see the most recent posts through sheer brute force? Ha, no.

Instagram will, eventually, stop showing new posts. On any hashtag with tens of thousands of posts, you’ll likely only see a small fraction of them — and that’s by design. Or, said another way, Instagram is directly burying content that users explicitly state that they wish to see. Essentially, your visibility into a particular hashtag is limited to what Instagram will allow.

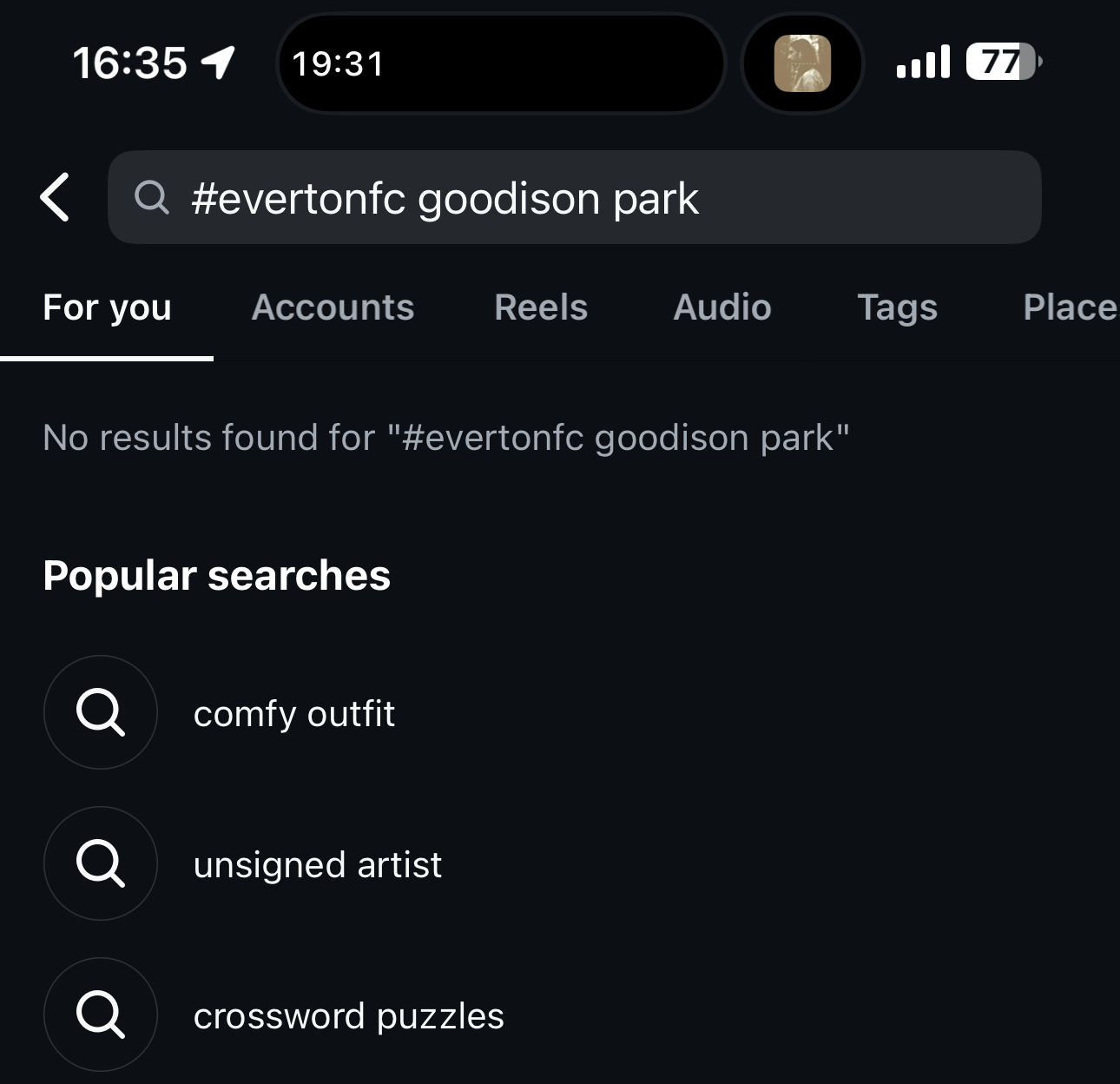

Additionally, users can’t refine their search by adding an additional term to a hashtag. If you type in “#EvertonFC Goodison Park,” it’ll reply with “no results found.”

Everton is, for those unfamiliar with English association football, a mainstay of the Premier League, and Goodison Park is the stadium it used until this year. There should be thousands of posts that include these terms. It’s like searching for “#NYYankees Yankee Stadium” — something that you’d assume, with good reason, to have mountains of photos and videos attached to it.

Additionally, when you search for a hashtag on Instagram, the app will show you content that doesn’t include the hashtag as exactly written, but has terms that resemble that hashtag. As a result, hashtags are effectively useless as a tool for creating taxonomies of content, or for discoverability.

Most of the points I’ve raised haven’t been covered anywhere — save for the initial announcement that Instagram would be discontinuing the ability to organize hashtags by date. And even when that point was mentioned, it was reported as straight news, with no questioning as to whether Instagram might have an incentive to destroy hashtags, or whether the points that Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri would later make (that hashtags were a major vector for “problematic” content) were true.

When Moseri would later say that hashtags didn’t actually help drive discoverability or engagement, that too was repeated unquestionably by a media that, when it comes to the tech industry, is all too content to act as stenographers rather than inquisitors. It’s a point that’s easily challenged by looking at the Instagram subreddit, where there are no shortage of people saying that the changes to hashtags had an adverse impact on their businesses, or their ability to find content from smaller creators.

I appreciate that I’ve ranted quite a bit, but I want to point out that there’s a broader theme here: that the Internet (or, at the very least, the tech giants) is, by design, increasingly hostile to the idea of content preservation.

We’ve seen Reddit stop the Internet Archive from preserving threads, in order to protect its ability to sell user data to giant AI slop factories. We’ve seen Facebook delete — for no reason whatsoever — countless hours of live video content. We’ve seen Instagram make it effectively impossible to search for content on the platform.

And I could go on. Google doesn’t work any more. YouTube and TikTok both have atrocious search tools.

This matters because — as I pointed out in my last newsletter — the division between our online and our digital lives is rizla-thin. If we accept — as I believe — that the Internet is real life, then it follows that the preservation of online history matters just as much as the preservation of history in the physical world. A healthy internet should allow for that preservation to take place — or, at the very least, not permit large companies to just erase or obfuscate vast swaths of history because it serves their interests.

The End of a Comprehensible Internet

Everything I’ve written so far has built up to my final, and most important, criteria on what constitutes a healthy Internet.

User-driven and driven by user-utility: The last point is obvious. The web is the product of the stuff that people do with it. As a result, any changes — whether the underlying technologies of the Internet, or the platforms that people use — should reflect that and help people do the stuff that they want to do.

Obviously, this is a point which the current incarnation of the web fails dismally to meet.

Previously, the Internet operated under its own law of physics, where things kind-of made sense. When you pressed a button that had a specific label, the website would perform whatever task was written on that label. Unfortunately, the rise of AI (the non-generative kind — don’t worry, I’ll get to that shortly) has effectively broken those laws of physics, with core web functionality deliberately broken in a drive to maximise user engagement at the end of the user experience.

Again, I talked about this a lot in my newsletter, Losing Control. I gave one example — how Facebook handles notifications, especially when the notifications are for a page or an account that the user has explicitly said they wish to see more from.

Let’s talk about notifications. You’d expect these would work… well, the same way that notifications work on any other application — by sending you a small alert when something happens, like when you get a message from someone, or a page you follow just posted a new update.

Nope! Facebook uses these as an algorithmic growth-hacking tool to increase user engagement, even if said engagement isn’t useful. You see this a lot with pages you follow, with Facebook issuing notifications for posts that are often several days — and sometimes even weeks — old.

I follow a page called 10 Ways that posts deals on online shopping. These are, by their very nature, time-limited. A store may sell out of a certain item, or on retailers that use dynamic pricing (like Amazon), the price may go up as people start buying the item in large numbers. To get the best bargains, you have to be fast.

Facebook’s algorithm, in its infinite wisdom, thinks it’s useful to send me links to posts that are several days old — and where the deals have since expired.

While you can tell the algorithm that you’d like to see more posts from a given page, this isn’t treated as a clear instruction to notify you immediately when a new post goes live. Rather, the algorithm takes it under advisement, and while it might show you more posts from said page, and faster, the extent to which this happens isn’t under your control.

That article gave plenty of examples, and after I finished writing it, I came up with more that I regret having not added.

For example, languages. If I search for something on YouTube or TikTok in French (which I speak pretty well) or Spanish (which I kind-of understand, but mostly when written down, or when a video is played extremely slowly), both apps will translate my query and include results that match the result in both the language my query was written in, as well as my native language, English.

From what I can tell, there is no way to turn this off — at least, completely.

Search, broadly speaking, is another great example of how the basic mechanics of being online are now engineered to disregard the stated intents of users. Every search tool, including those attached to major online properties like Facebook and YouTube, routinely disregard search terms — often at random — or change terms to include synonyms or different verb conjugations, often changing the meaning of the search phrase entirely.

And search tools don’t know how to say “I don’t know” — with the exception of Instagram, where you’ll provide it a query with likely thousands of matches, and it’ll just shrug and feign ignorance.

One of my favorite books of the early 2000s was Dave Gorman’s Googlewhack Adventure, which was later turned into a televised stage show that wasn’t nearly as good, but still worth watching if you’re at a loose end. The premise is simple: Gorman was on the hunt for Googlewhacks — people whose pages were the sole result when searching for two dictionary-standard English words, like “Francophile namesakes,” who he would then have to convince to meet up with him in-person.

Back then, you could do that because Google — and search products more broadly — knew how to say “I don’t know.” They provided an accurate record of what existed online, and if you knew the right words, you could easily find what you were looking for.

Now, Google — and, to be clear, literally every search tool provided by a large tech company — will adulterate your query with what it thinks you want. While you can (if you know where to look) tell Google to search for results that match your query verbatim, that option is buried where few will think to look for it, and it needs to be turned on for every. Fucking. Search.

And even if your search, with verbatim mode turned on, returns no results, Google will still show you a bunch of other “similar” content.

While I’ve ranted lengthily about several major tech companies and how, I believe, they dropped the ball, there’s a broader underlying point here. I don’t really understand how the web works, and I don’t think anyone — not even those working at these companies — does either.

The idea of an intuitive web — one where you instinctively know what things do, and can confidently predict the results of each action — died when tech companies shoved AI into features where, like notifications, it has no right to exist. And while these companies might insist that they did this for our benefit — and while idiot TechCrunch reporters will breathlessly repeat these claims because god forbid someone actually questions a tech CEO — the reality is that every change has served their own purposes.

A web that you don’t understand is one that’s not user-driven, or driven by user utility. It’s one where people don’t have agency over the technology they depend upon, and where changes aren’t contrived to address a specific user need.

At the risk of sounding as conspiratorial as the author of the original Dead Internet Theory, I believe the emergence of this incomprehensibility was borne of deliberate decisions made by people at the very top of Big Tech. Furthermore, I believe these people are profoundly anti-person, and see people as resources to be tapped rather than collaborators within a vast, global digital ecosystem.

In many respects, I think this phenomena is down to two things: first, many of the tech products we use were founded by people who were still in the throes of youth, and became billionaires and global tech icons before their brains were even fully developed. They’ve been insulated from people from a young age, never lived a normal life, and they’ve been told — repeatedly — that they are geniuses and visionaries. While I don’t think this explanation excuses any of their behavior, I also think it goes some way into explaining the scarcely-disguised antipathy these people show for their fellow humans.

When Mark Zuckerberg imagines a future where people have AI friends, the correct response isn’t to repeat his words in the front pages of the tech press. It’s to ask “who hurt you?” and to recommend a competent mental health professional.

The other factor behind this phenomenon is that many of the people running these companies are former management consultants spawned from hell (read: McKinsey) and then set loose on what amounts to “essential infrastructure” for the digital age. Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Google, is a former McKinsey consultant. Sheryl Sandberg, the former Chief Operating Officer of Facebook was one, too.

Management consultants have one job — it’s to recommend strategies to cowardly CEOs that they probably thought of themselves, but are too chicken to put their name behind themselves, that invariably screw over employees, consumers, and the planet.

People who work at these firms are typically recruited straight after graduation from the best universities in the planet — Ivy Leagues and Britain’s two hellmouthes of awfulness, Oxford and Cambridge — and then set loose into companies wearing ill-fitting suits that make them look like gormless younger brothers at a wedding, where they then suggest things like: “um, have you considered firing everyone and replacing them with a chatbot?” or “maybe we can boost sales of Oxytocin by partnering with McDonald’s and putting them in Happy Meals?”.

Management consulting is an industry where being a bastard — a real, unapologetic, shameless bastard, with no thoughts, care, or compassion to speak of — is a competitive advantage, and where the biggest bastards inevitably win promotions and climb the corporate ladder.

And so, it makes sense that some of the biggest anti-human moves — those that strip user agency and choice, and broadly sideline human thought and decisionmaking, including that from the users themselves — have been made at companies where these besuited sociopaths are in charge.

If I was Google’s CEO and someone suggested adding AI overviews to results, I’d object, if not for the fact that my entire business model relies on the existence of a healthy Internet — and one where Google hoards all the traffic and revenue is, by definition, unhealthy and unbearably centralized. (Hey! That was another one of my points from earlier!)

I’d also likely object based on the fact that generative AI presents a grave risk to user safety, especially on a site where people ask questions that have potentially life-and-death implications, like “hey, is this mushroom safe to eat?”

Like the internet, these people are incomprehensible, in part because they aren’t acting like humans — decent, moral humans — that exist in a society (as all humans do, Thatcher be damned).

A New Dead Internet Theory

If I was a doctor and the Internet was my patient, what would I hear if I put my stethoscope to their chest? Would it be a beating heart, faint and struggling though it may be? Or would it be a deafening silence?

Yeah, I won’t leave you hanging. I don’t hear anything.

It’s dead, Jim. And I believe it’s dead for a number of reasons, all of which I’ve mentioned above, but in summary:

There’s no common Internet experience any more — not even for those living in ostensibly liberal Western democracies like the UK. The underlying promise of the internet — the things you can do and the information you can access — isn’t enjoyed equally.

The Internet doesn’t just depend on a handful of large companies to keep things running. In some places, those companies are a mandated part of the infrastructure of the Web.

So much of what we consider to be the Internet exists within the purview of a handful of large tech companies, who are empowered to rewrite or erase history as they see fit.

So much of the internet exists in the open — in the clear — but is otherwise hidden because tech companies decide whether we get to see it or not.

Nobody really knows how the core mechanics of the web work any more, especially when it comes to the large companies that dominate the online sphere.

The people who are, for lack of a better word, running the web seem to genuinely hate people and would rather see humans as pure consumers, rather than people with specific needs that they use tech products to address.

Allow me to anticipate a criticism that this article may provoke. I imagine that some people might argue that I’m simply bemoaning the state of the current Internet, and if I believe that the web is dead, when was it ever alive?

It’s a reasonable point, and one that demands a response. I’d argue that 2011 represented a pre-rot Internet — the last truly good year before things took a turn for the worse. Facebook was yet to AI all the things. Google still worked. Apple made laptops that you could repair and upgrade. News sites didn’t geo-restrict entire continents. You didn’t have to let a shadowy company scan your face to read Reddit or send a DM to your friends.

If we’re to revive the Internet — or, at least, the promise of the Internet — we have to accept that things weren’t always this bad.

We also have to recognize that rot is something that compounds. It starts slowly, and accelerates quickly and beyond control. Facebook first introduced its AI-driven timelines in 2012 — and they were unpopular, but not enough to justify the kind of unhappiness we see now.

Over the next five years, Facebook gradually sidelined those in your personal network in favor of content from across the platform, and with each turn of the wheel, the app that was once the first thing you looked at in the morning became the equivalent of a Taboola chumbox.

As I wrote in Losing Control, Meta pledged — repeatedly — to tone things down, and to put humans back in the wheel, but never actually doing so. Eventually, it stopped bothering to even make those promises, and people just resigned themselves to their fate as the unwilling recipients of Q-Anon spam and AI slop.

It was a poignant lesson on how rot is, without fail, always terminal. Like a bit of black mould on a cherished t-shirt that you kept in the back of a closet, when it sets in, it probably can’t be saved.

Can We Revive the Web?

Okay, so the Internet is dead. Its corpse is on the pavement and its heart isn’t beating. Can it be revived? Is it worth locking lips and providing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation? Should you get the paddles out?

That depends.

I believe that the companies most responsible for the death of the Internet did so because they were motivated more by short-term financial results, and less willing to consider the long-term health of the Internet as an ecosystem where people and companies participate. They refused to accept that the Internet could exist at the same time as an oligopaly, where a handful of companies wield absolute control, and consume all the resources while leaving only a few crumbs for everyone else.

I don’t see that changing. Ever.

I’ve used Facebook all my adult life. I started using Google in high school. While, in any other context, that would imply some degree of loyalty, the truth is that I don’t see how these companies ever get better. I don’t believe they can be reformed, and I think that — under the right circumstances — a replacement could do a better job than them.

It’s funny. The other day, I saw a comment on a Reddit post about AI replacing jobs that said something like: “Tech CEOs don’t predict the future. They write it. When they say that AI will come for your job, they’re saying they’re building an AI that will take your job.”

I think that’s, perhaps, being a bit too charitable to the likes of Sam Altman and Masayoshi Son (to name just two examples) who are, depending on your interpretation, liars, idiots, or idiot liars. But the underlying point is there. When a tech CEO says something’s coming down the pipeline, they’re not basing that statement on any research or analysis, but rather they’re trying to will a future into existence through rhetoric.

Sometimes it works. Sometimes it fails, as we saw with the metaverse, which I’d argue was a perfect demonstration of how the people running these companies don’t understand what normal people want, need, or do.

But here’s the thing: I don’t believe that power of manifestation is limited exclusively to the types of people who drive Koenigseggs and wear patagonia vests in the middle of summer, in an aesthetic that can best be described as giving a kind-of “my kids no longer talk to me” vibe.

I have it. You have it too. We all have it.

You hate the modern Internet? Me too. Let’s build something better, together. Something that serves our needs, and doesn’t hinder them. Something where people have a stake, and ownership, and a sense of sovereignty that the modern tech industry has fought so desperately hard to suppress.

There’s no big, long-term plan required. Just a series of small, active steps that, when scaled to millions of people, add up to something that’s meaningful and profound.

Learn to identify rot when it sets in: Like I said earlier, when a company starts to degrade its products, the odds of it reversing course are next to none. I also pointed out that the first signs of rot are often subtle, and are designed to pass by unobserved, turning users into frogs in a slowly-boiling pot of water. The sooner we notice these changes, the sooner we can divest ourselves from these companies and move somewhere better.

Demand the media does its job: The tech media has an important job, and there are some incredible tech journalists working today. But there are far too many that are simply regurgitating press releases. When a company announces a change that’ll screw over their users, they amplify the message but never question it. Next time you see someone give a tech company a free pass, insist they explain why.

Get politically involved: Two of the most consequential pieces of legislation (at least, when it comes to the equality of information and equality of experience) were passed in the past decade. I can’t help but wonder how these laws would work if they weren’t crafted in parliaments that closely resemble a nursing home for the damned. The fact is, we need people — people who understand technology, and perhaps grew up with it — to get involved. To vote. To stand for office. To write to their representatives.

This need is especially urgent now, as governments start crafting laws for the benefit of the generative AI industry. In the UK, the Labour government’s stance is effectively to make theft legal if your name is Sam Altman and Dario Amodei.

Meanwhile, last month a man was jailed for three years for running an illegal streaming service that provided access to copyrighted content. Rules for thee, not for me, eh?

Notice the good: You know how Facebook insists on opening links within the in-app browser, and there’s no way to turn that off (except within direct messages)? That’s so that it can track your activity and target ads to you. Bluesky — a service that I love — allows you to open every link with your external browser.

Bluesky also has a chronological, non-manipulated timeline for its posts — making it feel like Twitter before it started its own terminal decline in 2016.

It’s just as important to notice the good as well as the bad, so that you can make informed decisions about what products to use, and which platforms get your attention — and the most limited of your resources, your time.

When a CEO says they “fucking hate generative AI,” as the CEO of Procreate said, and promise not to ever incorporate generative AI into their products, give them your money.

We win by making enshittification doomed to failure both in the long and the short term.

Make yourself rot-resistant: In proprietary software and services, there’s no way to guarantee that they won’t, eventually, start to exhibit the anti-user patterns and tendencies that we’ve seen elsewhere. The only real approach is to embrace open source where possible, and where you have to engage with the commercial sphere, choose companies you feel most confident that they have your best interest at heart.

If you’re using an older PC and Microsoft is insisting you buy an entirely new machine for Windows 11 — an OS that makes it hard to use without also creating a Microsoft account, and that slurps up your data at every given possibility — look into installing something like Ubuntu or Linux Mint, both of which are extremely user-friendly.

Need a new computer anyway? Get one from an ethical company. Purism sells Linux machines that are hardened against surveillance by default, and even disable the Intel Management Engine (IME) — a computer within your computer, essentially, with all the privacy risks that entails.

If you’re in the UK, switch your ISP to Andrews and Arnold.

I fucking love these guys. They’re a bunch of privacy-conscious nerds running an ISP out of a shed in Bracknell (I write that will all the love in the world, and not as a pejorative), and they’re one of the few ISPs to guarantee that they don’t track or surveil their users, and they limit censorship to that mandated by law.

Also, if you’re a competent human being who understands technology, they won’t patronise you and insist that you restart your router before actually thinking about your problem. They’re prepared to meet you where you are.

They also don’t do any nasty packet-shaping or anything that results in weird, skewed peak time performance. They’ll deliver speeds as close to those that you were promised.

They’re expensive though — but I’d argue they’re worth it.

Sadly, where I live essentially requires that I use one of the UK’s worst ISPs (no, not Talk Talk. Even worse, if you could believe it), and so I haven’t been a subscriber for several years.

If I had the choice, however, they’d have all my money.

If you have to use proprietary software, try to buy it, rather than sign up for a subscription where the functionality can be withdrawn or changed at any given moment.

Mastodon might be a bit complex for the average person, but Bluesky is a great alternative to Twitter and Facebook. Seriously, it’s highly recommended. And it’s a public benefit corporation.

Be vocal: Part of the reason why the Internet’s fallen victim to endemic platform-level enshittification is because people are resigned to its inevitability. We should never stop shouting that things suck, and things can be better.

Don’t forgive and don’t forget: The people who are responsible for the death of the Internet have names — Sundar Pichai, Adam Mosseri, Mark Zuckerberg, Prabhakar Raghavan, Satya Nadella, Sam Altman, Elon Musk, to name but a few. Never forget their names, and when they try to convince you about the “next big thing,” or that they’ve somehow changed, don’t believe them.

Ask why: Remember how I said that tech doesn’t predict the future, it invents it? Next time someone tries to tell you how something will be the next big thing — whether that be generative AI or the metaverse — ask why? What’s the long-term implications of a new technology, and how does that person benefit from you being excited about it, or convinced of its inevitability?

Make fun of them: I’m going to repeat Ed Zitron’s advice here. The people who are responsible for ruining the web also believe that they’re visionary geniuses who are remaking the world for the better. They also have the thinnest skins imaginable. The easiest way to shatter the image they want to project is to point out how ridiculous it is, and how ridiculous they are.

This is a bit of a side-note, but I actually have a fun story to share here. About a decade ago, I was at a dinner in London that brought together people in tech media and startup founders.

The wine flowed. One guy said, in a loud and clear voice, how his startup was singularly instrumental in the ousting of Libyan dictator Colonel Muammar Gadaffi.

What did it do? Smart bombs? Killer robots? Hackable fembot assassins, a la Austin Powers?

None of those things. He had a website where you could watch CNN and Al Jazeera through your browser. Which, I guess, in an autocratic society with a tightly-controlled press, might help a bit. But to say that you’re singularly responsible for ousting Gadaffi?

Unless your startup is called Raytheon, pipe down.

Own your stuff: This point is something that I’ve argued previously, but the current incarnation of the tech industry has sought to eliminate any notion of ownership by imposing restrictions on what people do with their own property, and by pushing people to subscriptions.

It’s time to bring back physical media.

It’s also time to recognize that anything you’ve saved on the cloud is, not entirely, yours. There’s always a prospect that, due to forces beyond your control, you lose access to your stuff.

External hard drives are cheap. Hell, you can get really a 2TB portable SSD for around £75.

Protip: yt-dlp is an amazing tool for grabbing video files from the web, especially from platforms that — by design — make it impossible to save content for offline usage (especially without paying for the privilege).

Make sure that you’re saving stuff in a place where only you have access to it. Not only does this prevent the tech industry from deleting your cherished memories whenever they need to juice their margins, but it also means that you can revoke access at any point — which is good when you consider that your data isn’t just your memories and your messages, but rather something that has value for generative AI companies.

Owning your own stuff, on hardware that you own, gives you a veto on how your stuff gets used by other companies. It’s as simple as that.

Embrace inconvenience: We surrendered our independence and our autonomy to the tech industry because they promised us convenience — a bargain that they are, it seems, no longer willing to uphold. If we’re to restore the web to its former glory, we need to acknowledge that liberating ourselves won’t be easy.

Moving to Bluesky will require you to build your contacts from scratch.

Linux has come a long way over the past decade or two, but it still has a learning curve — although you can quite easily do most things without having to type a command into the terminal.

Supporting companies that respect your rights as consumers and individuals might mean that you pay more (as with the ISP mentioned earlier) or that you have to re-learn things that are muscle memory.

It might suck for a bit! But remember why you’re doing this.

Recognize your worth: As the saying goes: if you’re not paying for it, you’re not the customer, you’re the product. Big tech has commoditized humans just as easily as it hates them.

But here’s the thing — for these companies to be viable, they need us. We can live without Facebook. Facebook — or any other similar company — can’t exist without us. We hold all the cards.

The Internet is dead. Hope, however, is not. We can always build a new Internet in our own image — but only if we choose to do so.

Afterword

Good lord. This piece was more than 10,000 words. I don’t know whether Ed Zitron is a good influence or a terrible influence.

What We Lost now has over 750 subscribers. That’s insane considering that I published the first newsletter on June 18. That’s not even two months ago.

Even more insane: I now have 15 paying subscribers. To everyone who has decided to support this project, thank you.

If you liked this newsletter and want to support me, consider signing up for a paid subscription. You won’t get anything — yet — but I do plan to start doing premium-only newsletters when I cross the 1,000 mark.

Given how fast this newsletter has grown (I basically doubled my subscriber count in one month), that’ll probably happen within the next couple of months. And that’s where I’m going to post the stuff that’ll really damage my career prospects.

As always, if you want to get in touch, feel free to email me at me@matthewhughes.co.uk or via Bluesky.

The next post will be less dour, I promise.

I've always been astounded by the credulity and servility of tech journalists.

Way back in the early days of the modern internet, there was a lot of hype about "push". Basically, advertisers hated the internet because people would pull and get to see what they were looking for rather than whatever the advertisers were pushing. Only the advertisers, and advertisers are big drivers of just about every form of media, wanted push. Users didn't, and the internet let the pull what they wanted.

Pull continued to work until the various aggregators, search companies and social networks, decided to kill it. First, search eliminated textual search. They'd show you what they wanted to show you whether you asked for it or not. Marketing is a weird science. Imagine someone walking into a well marked candy store and heading for the chocolate and walnut aisle. You or I might imagine that they want some candy, probably chocolate with walnuts. Markets think differently, so they use complex surveillance and data analysis and know 100% for sure, so sure they'll bet money on it, that the guy in the candy store having chosen a pack of chocolate coated walnuts and heading for the cashier really wants to buy a pair of jockey shorts. Salivating at the thought of a delicious chocolate and walnut candy cluster, this guy is caught short when the cashier refuses his purchases and insists on selling him underwear. Monty Python comes to mind. "I'd like to buy this candy." "You don't want candy. You want underwear." This is why marketing people get the big bucks. Maybe, just maybe, they'll let the guy buy his chocolate covered walnuts if he buys a three pack of men's briefs.

Search was neutered a while back as part of the war on pull. Then, they developed algorithmic feeds which are just push of whatever they want to show you perhaps leavened with a bit of whatever one is trying to pull. The internet was about being able to pull up what you wanted, but this clashed with the business model. It has gotten so bad, that some of us are paying for search that lets us do what we used to be able to do for free 15 years ago. Maybe we'll see a return of pay to present social media in some form that offers a chronological feed with a search feature.

It's no surprise that the internet feels empty. Whenever one sinks a hook into it, one never gets a fish. One gets old tires and water weeds. Are there fish in the pond? Possibly, but you'd never know it if you try fishing.