How Silicon Valley and Big Business Created The Next Lost Generation

The kids aren't alright.

Note from Matt: Like everything I’ve published so far, this post is long — too long, in fact, to read in your inbox. To see the whole thing, click through to the newsletter in your browser or in the Substack app.

Earlier this week, I was listening to an episode of Oh God, What Now — one of my favorite UK politics podcasts — in my car. Halfway through the episode, the conversation shifted to why the 1990s were, in retrospect, seen as a golden era for young people, looked back fondly for reasons that go beyond the typical rose-tinted youthful nostalgia that you hear from those in their 40s and 50s.

It wasn’t just that the 1990s were seen as a kind-of cultural renaissance, especially in the UK, which was riding high on the “Cool Britannia” wave of the early Tony Blair years. It was a time when rent was cheap (one of the hosts mentioned paying £50-a-week in rent), and so you actually had money to socialize and do things.

The Internet, although very much a thing beyond academia and business, wasn’t a big part of our lives. The news cycle was slower — with each week often dominated by whatever investigation published by the Sunday newspapers — and the presence of things like print magazines and music charts marked the passage of time in a way that doesn’t exist today. The unspoken insinuation was that the kind of endless doomscrolling of today — where algorithms can, for an indefinite amount of time, remind you of how shit the world is — simply wasn’t possible back then, and people were happier and healthier as a result.

By contrast, younger millennials and Gen-Z are fucked. Cheap housing? No. The average rent for someone in England outside London jumped from £130-a-week in 2008/2009 to £191-a-week in 2023/2024. Meanwhile, salaries (when factoring in for inflation) have remained stagnant since the global financial crisis. With young consumers having less money to spend, nightclubs and bars are shutting down at record pace. The number of pubs in the UK shrunk by 15% between 2010 and 2019. The number of nightclubs halved between 2013 and 2024, falling from 1,700 to 787.

The end result is a generation that’s more insular. Isolation is at epidemic levels, with 70% of 18-to-24-year-olds reporting feeling lonely at least some of the time. Despite the proliferation of dating apps, more adults than ever are single — contributing to that epidemic of loneliness mentioned earlier. Marriage rates, though steadily declining since the 1990s, especially have plummeted since the Great Recession.

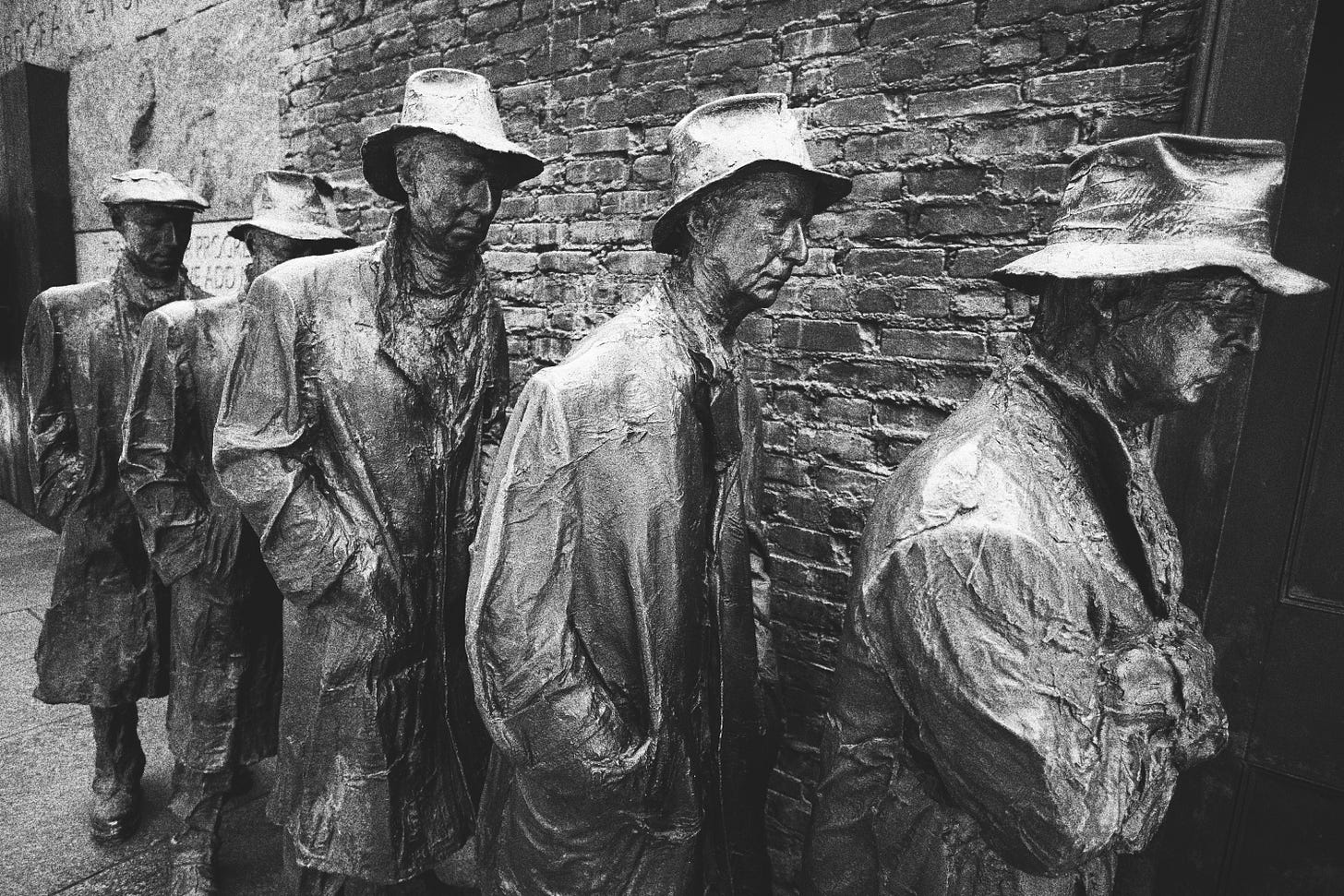

There’s a deep-seated unhappiness, especially among millennials, who feel as though their early adulthood lacked the halcyon days enjoyed by those younger millennials and Gen-Xers — those who enjoyed cheap rents, affordable housing, and the short-lived euphoria of the time when Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” felt real. This is a generation that never caught a break.

Millennial Malaise

Although half of my readers are from the US, I feel as though I need to explain why things are so dire in the UK, and why the malaise I’m talking about (at least, from my own experience) feels especially more pronounced over here.

I’m going to run you through the major milestones that have happened in UK politics since I turned 18.

August 2009: I turned 18.

May 2010: The UK holds a general election where the incumbent center-left Labour government loses power. The Conservatives — the party of Thatcher and consanguineous marriage — form a minority government with Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats.

This needs some context. A lot of people from my generation voted for Clegg as he represented the kind of socially-liberal policies that were lacking in Labour, while also supportive of the welfare state that people liked and wished to see protective. Clegg’s tryst with the Tories was seen as an act of betrayal, and one that took the Liberal Democrats more than fifteen years to recover from.

Clegg, incidentally, became Meta’s VP of Global Affairs and Communications in 2018, proving that there are no bastards too evil for him to work with. He was later promoted to President of Global Affairs, and this year announced he would leave Meta, presumably to make way for a Trump-friendly replacement.

November 2010: The UK government raises tuition fees to £9,000 — or roughly triple the previous amount.

In practice, this meant that anyone who goes to university faces the prospect of accumulating more than £50,000 in student debt.

The Lib Dems, I note, previously campaigned on the abolition of tuition fees, making higher education free, just as it was before 1998.

When students protested, the London Metropolitan Police responded with tactics you’d expect to see in Putin’s Russia, not a Western liberal democracy. Protestors were “kettled” by police — effectively kept in place and unable to leave, except in a slow, controlled trickle — and deprived of food, water, or toilets.

Those kettled, I add, included 11-year-old schoolchildren wearing their school uniforms.

May 2010 to May 2015: I feel as though it’s important to note the various other shitty things that the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition did during this period.

Introduced a “workfare” program that forced unemployed people to work at for-profit businesses to receive welfare benefits. This included forcing a STEM graduate to work for Poundland — the UK equivalent of Dollar Tree — for £63-a-week.

Eliminated the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA), which provided cash payments to 16-to-19-year-olds from low-income households in order to support the cost of remaining in post-16 education.

Embarked upon an austerity program that led to the closure of 800 libraries between 2010 and 2021 and slashed arts and culture spending by 17% between 2010 and 2016. The effects of these cuts were not shared equally, with places like Northern Ireland disproportionately affected.

Eliminated bursaries and fee-free education for medical subjects (like nursing), where students, as part of their course, work for free at hospitals.

Imposed a benefit cap that limits everything a recipient may receive — from unemployment benefits to subsidized/state-funded housing — to £20,000 (£23,000) in London. In expensive housing markets, this had the effect of displacing people from their communities, or pushing them into sub-standard housing.

This, combined with other idiotic policy decisions — like limiting the ability for local councils to raise debt to pay for affordable housing — led to skyrocketing homelessness rates.

In 2012, Parliament introduced punishing new income requirement requirements for family visas, effectively putting a “tax on love.” If you fall in love with someone outside of the EU, you’d best not be poor.

These requirements were increased to £29,000 in 2024. That figure is lower than the average salary in some regions, like the East Midlands and the North East of England, and entry-level salaries are often well, well below that figure.

This policy has effectively stopped people from living with the people they love, creating an entire generation of babies who only know one of their parents through Skype.

I’m going to stop now, not because I don’t have enough material to talk about — I do — but because it’s depressing me.

May 2015: The Conservatives narrowly win a majority government, allowing them to rule without even the modest restraints imposed by the Liberal Democrats.

December 2015: Parliament passes the European Union Referendum Act, requiring that the government hold an in/out referendum on EU membership by 2017.

June 2016: The UK narrowly votes to leave the EU by a margin of 3.78%.

Exit polls reveal that every age group between 18-49 wanted to remain, with 71% of 18-to-24-year-olds voting to remain.

For young people, this was an act of supreme generational unfairness, with the gerontocracy choosing to strip away the benefits of EU membership from those who actually wanted them.

Many of those Leave voters are now dead. One analysis from UK in a Changing Europe shows that the post-Brexit majority for Remain is, in large part (though not entirely), driven by “voter replacement” as those Leave voters die off.

Put another way: A whole bunch of people voted for something that they themselves wouldn’t live to see the consequences of.

January 2020: The UK finally, after almost four long years of brutal negotiations, leaves the EU. This starts a one-year transition period, before the effects of Brexit are realized.

Brexit ends the right of Brits to free movement. Previously, you could work, study, or retire in any EU country without having to obtain a visa. Now, Brits are treated as any other third-country national.

This also goes both ways. EU nationals can no longer move to the UK visa-free. Fall in love with a French girl, or a Spanish boy? You now have to meet the income requirements and pay thousands in visa costs.

I’m not kidding about the visa costs. My wife is American. Every two-and-a-half years, we’d have to scrape together £2,500 to pay to renew her visa.

Fortunately, she obtained permanent residency last year, meaning we no longer have to deal with that stress and cost.

The UK withdrew from the Erasmus program, which allowed UK students to spend a period of time studying abroad within the EU and other participating nations. This is replaced by the “Turing Scheme,” which doesn’t actually pay for much at all.

Brexit also ends free roaming, meaning that you can no longer use your cell phone in Europe without paying much, much more for the pleasure.

Although the UK has a (barebones) trade deal with Europe, which is Britain’s largest import partner, it imposes certain bureaucratic costs that result in price increases for food and other living essentials.

The post-Brexit deal doesn’t include a provision for continued provision in Horizon 2020, an ambitious package of investment for science and technology research. It rejoins the program in 2023 — although those three years represented a massive opportunity cost for the UK’s tech and science sectors.

March 2020: The UK enters lockdown, and doesn’t fully emerge until July 2021, with masking requirements remaining in force until January 2022.

As with everywhere else, the pandemic saw young people forgo the normal activities of youth — studying in a classroom, travelling, going to bars and nightclubs, going to concerts and festivals — to protect the immunocompromised, and to a much greater extent, the elderly.

It was a sacrifice that, frankly, wasn’t recognized.

Young people — and especially young men — were, however, significantly more likely to receive fines for breaches of lockdown regulations. Those from minority ethnic groups, as well as lower income groups, were also more likely to receive fines, which could be as high as £10,000.

February 2022: Russia invades Ukraine, with global consequences. As with every other country, the cost of energy and food soars in the UK, making every day feel even more like a struggle.

September 2022: Kwasi Kwarteng, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in Liz Truss’s short-lived government, unveils his mini-budget — nicknamed the Kamikwasi Budget — which immediately implodes the UK economy. Mortgage rates soar, as do rent prices. The Pound reaches all-time lows, further accelerating inflation.

July 2024: The UK goes to the polls again and, for the first time in nearly two decades, gives the Labour Party a majority. Finally, a break from Tory Party Thatcherism, right? Things can only get better?

Ha, no.

For those in my age group, there has never been a time when things were “good.” We never had the equivalent of the post-Bush Obama years, when there was hope that society would be less stacked against us. I believe that constant faltering — from generationally-imposed shitshow to generationally-imposed shitshow — has, in some way, altered the British millennial psyche, turning those in my age cohort cynical and, frankly, really fucking depressed.

Part of that malaise is, in part, because the crises we’ve seen — the awful, authoritarian, neoliberal governments we’ve suffered — were ones that we didn’t vote for, and didn’t want. They were imposed upon us by a generation that didn’t have to worry about the cost of education, or buying a house, or finding somewhere affordable to rent, and that benefited from the post-WW2 social safety net.

Brexit was something that old people voted for. It did not have a majority among those under 49. The Tory Party has always been the party of statin-swallowers, its parliamentary majority always one heatwave away from oblivion. One cold snap, and it’ll be holding its next conference in the inner rungs of Hell.

Everything that I wrote about above is something that we didn’t want, but that was imposed upon us, or, in the case of Covid, was a pandemic where the young made some of the largest sacrifices (in terms of forgoing life’s milestones) with little-to-no recognition or appreciation.

I’d also argue that the persistent electoral failure of those we hoped would change the unhappy status quo led to the cynicism that drips out of every millennial pore. This was a generation that pinned its hopes on candidates like Ed Miliband, Jeremy Corbyn, and Bernie Sanders, and on the perseverance of the Remain campaign, only for them to be vetoed by the gerontocracy.

Things have never been good for my generation. If the 1990s was the End of History, as Fukuyama put it, then early millennials are the group that learned that history fucking sucks, especially when you’re, demographically, on the wrong side of it.

And that’s why I’m terrified on behalf of the next generations — Gen-Z, Gen-Alpha, and everyone else that’s only just entered the workforce, and everyone that will in the coming years — because as bad as things were (and are) for us, they’re only going to get worse.

To quote the poet Philip Larkin: “Man hands misery onto man. It deepens like a coastal shelf.”

I’ll… uh… let you look up the rest of that poem in your own time.

When Compounding Generational Misery Meets Big Tech

In 2015, when reacting to the Conservative Party victory at that year’s general election, the Scottish comedian Frankie Boyle quipped: “We’re about to birth the first generation of babies that will be regularly awoken to the nocturnal screams of their parents.”

He wasn’t wrong, but what he didn’t say was how that generation would have it even worse — and the role that big tech and big business would play in the emergence of an intractable generational misery that will be passed down from parent to child, like a family heirloom. Similarly, this misery won’t be contained to the rainy, grey shores of Britain, but will be felt throughout the industrialized world. As bad as things are today, they’re only going to get worse.

I’m confident about this for two reasons:

Firstly, I recognize that decisions made in politics can have generational — and often unforeseen — consequences that aren’t easily remedied down the road. The UK is a shining example of that, with Thatcher-era policy decisions on housing and energy playing an ongoing role in the current (and seemingly never-ending) cost-of-living crisis.

Secondly, the capricious anti-worker tendencies that asserted themselves during the Reagan years — and especially during Jack Welch’s reign of terror (or should that be error?) — never went away, and have only gotten worse in the past decade-and-a-half. Whatever social contract that may have existed between employees and their employer at one point has now, forever, gone. I’m not sure how, in an era of outsourcing and artificial intelligence, it can ever be restored.

Forgive me. The next paragraph will be perhaps the bleakest I’ve written so far — and perhaps the bleakest I’ll write in this newsletter — but I feel a duty to be honest with you, even if that honesty is uncomfortable, if not deeply unhappy.

The next generation is screwed. As bad as we had it, it’s only going to get worse. Forget about employment rights, or rising living standards. Forget about a dignified, secure life, where people can afford to pay for a decent home. The state won’t be able to help them. They will never know secure employment. The era of the job where you join after university, and then leave to enter retirement, was on life support for a long time, but now it’s completely dead.

Although short-sighted policy decisions — or policy decisions made for the benefit of a handful of extremely wealthy individuals and corporations — will play a major role in this sorry state of affairs (as they have previously), arguably the biggest factor in the eternal generational misery I’ve described isn’t necessarily how politics is polarized when it comes to age, but because of the decisions of the tech elite.

Artificial intelligence — and especially generative AI — will be a major driver of the employment insecurity that we’ll see in the coming years and decades. Before you accuse me of contradicting the point made in the previous newsletter — where I asserted that AI won’t take your job because it can’t do the things that its boosters have promised — I think I should clarify my position.

AI won’t directly take jobs. For evidence of that, we only need to look at the frosty reception to OpenAI’s long-awaited GPT-5 model, and the immediate signs that it wasn’t, in fact, a measurable step forward in capabilities. The underlying flaws in LLMs that make them unsuitable for anything important or sensitive are just as visible in GPT-5 as they were in previous models, and there are no signs that the hallucination problem will go away.

I do, however, believe that the perceived fear of AI — at least, while the mythos perpetuated by charlatans like Sam Altman and Satya Nadella persists, and remains unchallenged by a captured and credulous media — will be a major driving force in employment insecurity, as it’s the perfect excuse for layoffs and outsourcing.

I’m not predicting anything here, insofar as I’m arguing that a trend that we see today will continue indefinitely into the future — at least, why for as long as the hype surrounding artificial intelligence persists.

While we can identify specific examples of where a company has announced layoffs due to AI efficiency — or timed around announcements that proclaim how AI has reduced the amount of human labor within an organization — only to hire in cheaper labor markets, it’s probably more useful to look at aggregate trends.

My thesis is simple: If AI was, in fact, reducing the need for human labor, we’d see declines in revenue in the big five “body shop” outsourcing companies. These five companies are known as WITCH companies — an acronym that stands for Wipro, Infosys, Tata, Cognizant, and HCL. All of these companies are publicly traded, and in their latest annual reports, we can see the following revenue changes.

Wipro (down 2.3 percent)

Infosys (up 6.1 percent)

Tata (up six percent)

Cognizant (up two percent)

HCL (up 6.5 percent)

Four out of the five WITCH companies grew their revenues at a time when, purportedly, generative AI was rendering human labor obsolete. Three of those businesses grew at a rate of six percent, or higher. For context, Apple grew by two percent year-over-year in 2024.

How do you square that particular circle? These are incredibly labor-intensive companies. Infosys, according to its most recent annual report, employs 320,000 people. Cognizant employs 336,800. Therefore, you’d assume they’d be most impacted by labor-saving technologies (especially those developed by large American companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, and commoditized by smaller, mostly-American companies like Anysphere and Replit).

If GenAI did the things it could, these outsourcing “body shops” would be the Blockbuster Video of the AI era, with OpenAI and Anthropic being the Netflix that takes them behind the barn and puts them out of their misery.

Another important stat to consider: If generative AI was actually driving layoffs, why did OpenAI only make around $1bn from API services in 2024? This is around one-twentieth of Cognizant’s revenue. And that’s just one company!

Sidenote: I didn’t compare OpenAI’s revenue against every one of those WITCH companies for a simple reason: namely that Cognizant, as a US-registered company (albeit one where the majority of its workforce is based in India), reports its revenues in US dollars. Some of the other companies mentioned report their turnover in rupees, which would require me to figure out the exchange rate for each company, at the specific times in which they reported their financials.

That being said, I wouldn’t be surprised if the total revenue was 1:100 in favor of the combined WITCH companies.

Outsourcing has always been unpopular — and the more egregious examples, where laid-off employees are forced to train their replacements in order to receive any form of severance, regularly attract negative media coverage. These stories were regularly repeated during the 2016 Trump campaign — and I’d argue they played a role in making Trump’s blend of nativist populism palatable for many of the college-educated, middle-class voters that lent him their support.

I’ve pointed out, time and time again, that AI is the perfect cover for this practice, and I’d argue that it’s because of a complicity within the media where they’ll happily report the initial story (“X thousand workers laid-off because of AI”), but never ask the follow-up (“hey, why are you hiring the same number of workers, doing the same roles as the people you just fired, in this massively cheaper market?”).

It’s interesting to note that, before Jack Welch, layoffs were seen as somewhat of a taboo in the business world — something not celebrated as a company “downsizing” to increase profit margins or “drive efficiencies,” but rather as a troubling red flag. An indicator that said company was, in fact, in trouble and was shedding headcount as a means to stay alive.

The post-Welch changing of the narrative surrounding layoffs has meant that when a company fires tens of thousands of workers, it’s celebrated, particularly in the stock market. In 2022, when Meta announced it would fire 11,000 workers — or 13 percent of its workforce — the market responded positively, with its share price jumping by 5.2 percent in one day. Shares in Spotify jumped 7.5 percent when it announced it would fire 17 percent of its workforce.

The problem with layoffs — and with outsourcing — is that it’s unpopular. For companies trying to control the narrative, AI is incredibly useful as it feels (in no small part thanks to the mythology crafted by Altman and Amodei and other ghouls) inevitable, just like how automation and technological advances resulted in workforce reductions in other industries, like textiles and car manufacturing.

AI was a gift from Big Tech to Big Business that allowed them to fire, and slash, and downsize with impunity. It shifted the conversation from shareholder value to the inevitable march of technological advancement. It is perhaps the most evil thing the corporate world has done since the invention of leaded gasoline and PFAS chemicals, and if hell exists, I hope to see every Patagonia-wearing dickhead that’s served as an apologist for generative AI there.

Another concern I have is that generative AI — or, rather, the fear, however unfounded, of generative AI — will result in a precipitous drop in bargaining power for those workers yet to be replaced by their offshore counterparts.

Asking for a raise, or better working conditions, will be a lot harder when you’re convinced that the only reason you haven’t been replaced by an LLM is because of the good graces of your employer. So, why rock the boat? Why ask for a raise that actually keeps pace with inflation? Why ask for more days off, or the freedom to work from home? Why join a union? Why go on strike?

I fear that the mythos surrounding AI — which, I believe, will persist long after the inevitable collapse of OpenAI and Anthropic — will only deepen the workplace serfdom we see today. And it’s not like things were already that great.

US wages stopped keeping pace with productivity in 1979. The emergence of the gig economy — as well as the replacement of employees with contractors — created a class of workers that had all the hallmarks of an employee, but with none of the rights. Whereas a pizza delivery guy might have made minimum wage plus tips in the 1990s, today they’re likely beholden to whatever work Ubereats, or Postmates, or Deliveroo sends their way, while also forced to pay for the cost of actually doing their job — whether that be gas, or insurance, or wear-and-tear on their vehicles.

Separately, I also fear that as unhappy and lonely the current generation may be, future generations will be unhappier and lonelier.

Part of this will be down to sheer economics. You won’t go to a bar with friends, or to a sports game or concert, if you can’t afford the ticket, or the price of beer, or, in fact, if the bar itself has closed down. Or, for that matter, because you’re doing gig economy work as a side hustle because your day job isn’t enough to pay the bills.

As our societies get poorer, while the cost of living remains the same, I fear we’ll see a generation of economically-driven hikikomori. Hermits, not because they choose to be, but because that’s how their life is.

Another factor that will drive this antibiotic-resistant strain of loneliness is the prevailing growth-of-all-costs mindset in Silicon Valley. For what it’s worth, the Internet is real life. Social media is real life. It’s been that way for more than a decade now, and to pretend otherwise is, at best, naive, and at worst, oblivious to the way the world works.

While some may dispute this — and I’d understand why — I believe it’s possible to have a healthy social life, and healthy relationships, that exist primarily in the digital realm. I base this view on my own personal experiences.

My wife, as mentioned earlier, is American. For the first two years of our relationship — including one-and-a-half years when we were engaged — we were long-distance. Most of our interactions, outside the few weeks a year when we could meet up in the States or Europe, were online. Every job I’ve ever had since leaving university has been remote. A life lived online has meant that the majority of my friends live throughout the globe, from America to Australia, and everywhere in between.

In the past, Facebook and Twitter did a great job of actually connecting you to the people you cared about. This has, naturally, changed since the emergence of algorithmically-driven timelines intended to maximize engagement — even if doing so means that you don’t see posts that your friends and family share.

To quote myself in Losing Control:

When I say the News Feed is “dominated” by digital detritus, I’m not exaggerating. As an experiment, I just opened Facebook on my laptop’s browser and decided to count how many posts I would have to scroll through before I saw something from a person I knew.

Seven. Seven posts. There were a couple of ads, one from the CIA, one from Facebook itself, and another from Rabbi Schmuley Boteach. No, I don’t know why either.

I opened Facebook on my phone and was similarly confronted with random posts — one from a Canadian MP somewhere in Ontario, another page that exists to mock people working in service jobs, and a random post from a group where people post pictures of the in-flight meals they’ve enjoyed.

Given that I am neither Canadian, nor a sociopath that derives pleasure from making fun of poor people, nor someone who particularly enjoys convection-heated lasagna served on a plastic tray, I have no idea why I was shown these posts.

This change is emblematic of the death of social media. Facebook isn’t a social media company any more. It’s a content consumption platform — just like TikTok — that masquerades as a social media platform.

Technology was once a tool that facilitated the creation and maintenance of fulfilling, meaningful relationships. No longer.

And so, why wouldn’t you feel lonely if you opened Facebook and, instead of seeing pictures of your friend’s new baby, or what your cousin had for lunch, you were instead bombarded with pictures of Shrimp Jesus and rage-bait articles from pages you’ve never previously interacted with?

And how wouldn’t this contribute to the endemic feeling of loneliness that we see today, not just within millennials, but also within Gen-Z and Gen-A?

A person’s online life is their real life. But what separates the virtual world from the physical is the ability for a third-party — in this case, the platforms that facilitate online interactions — to curate and manipulate the entire experience for their own benefit.

A good analogy would be to imagine you went to a bar with your friends, but the bar picked which friends you could invite based on how much money its managers expected they’d spend. Or, better yet, disinvited some of your friends and instead invited a bunch of people with drinking problems.

We wouldn’t accept this in the physical realm — or, to use a term that I fucking despise, meatspace — but it’s an accepted and inevitable reality of the online world. In that sense, millennials are lucky, insofar as they remember a time before social media was so aggressively manipulative. The youngest generation online today — and those who come after — will never know any different.

It’s messed up. If you accept my point — that the online world is the real world — it’s not hard to take the next step: that online platforms can be a tool to reduce loneliness, or they can choose to exacerbate it, and most have chosen the latter with zero consequences and zero remorse, and they will continue to do so.

You Need To Realize How Bad This Is, And How Bad It’ll Get

Millennials are paradoxically seen as the most pampered, entitled generation — the “flat white and avocado toast” generation, if you’re a Daily Mail-reading moron — and yet, empirically, are the unluckiest generation that peacetime has ever known.

They came of age during an economic crisis that we’re still — nearly two decades later — trying to recover from. Those born in the UK had to reckon with fifteen years of Tory Party austerity that shredded the welfare state, as well as any semblance of economic growth or rising living standards.

Then came Brexit, and Trump, and Covid, and Trump again, all while the basic costs of living soared, entirely for the benefit of an affluent gerontocracy that had already benefited from the programs and institutions they voted to destroy. While I’m not denying other generations had it rough — I wouldn’t have wanted to come of age during the Vietnam War, or the stagnation years of the 1970s — at least things eventually got better.

Millennials are still waiting. And, frankly, they’ll keep on waiting, because the factors that directly caused their generational malaise aren’t the byproduct of singular decisions, but compounding decisions made by previous governments with no concern or thought for the future, or even for the people they purported to represent. I don’t believe that things will get better for me, or for my generation, and I’ve come to terms with that. I’m past the bargaining phase of the grief cycle, and I’ve skipped right to acceptance.

I also believe that the misery that millennials faced — and continue to face — will pale in comparison to what the next generation will experience.

Future generations will be lonelier, poorer, and unhappier than any other in living memory, and while this is, in no small part, due to the historic policy choices I mentioned earlier, I also believe that this misery will be driven by the mendacity of an AI-obsessed Silicon Valley and the capriciousness of a business world that sees no obligation to their employees or their communities, and concerns itself only with the two most evil words known to mankind: “shareholder value.”

We should care about this because we care about people. We care about our fellow human beings.

But we should also care about this because, inevitably, it affects us all. You may have kids — or plan to have kids — that’ll grow up in the hellscape I described. The evisceration of the post-War social safety net, and the shredding of the employer-employee social contract, means that they’ll depend on their parents more than any generation previously.

I write this because I don’t want you to be unhappy, or insecure in your home or job, and I don’t want that for your kids, either. I’m sure you feel the same way.

If nothing else, we should also care because, frankly, nothing good has ever come from a generation that’s disenfranchised, impoverished, and that will never know the security of a stable job, or a home that they own, or a home where the rent marches upwards at a pace far beyond their pay-packets.

Nothing good has ever come from a generation that’s been dealt a bum hand in life, and that sees no remedy through politics. Where the factors contributing to their unhappiness seem so entrenched, there’s no way to fix them through the ballot box — or, equally bad, they’ll pin their hopes to an authoritarian figure that promises that they alone can fix the problems in their life, so long as they’re free to do what needs to be done with no checks or balances. Sound familiar?

The kind of economic insecurity and disenfranchisement I’m talking about, and that I’m utterly petrified of, has, far too often, led voters to a dark place. I’d argue that contributed to the decisions made by the British and American electorates in 2016 (and again in the US last year).

I need you to realize that no matter how bad things are now, they can always get worse. And if nothing changes, they will.

Footnotes

As always, if you want to get in touch, feel free to email me at me@matthewhughes.co.uk or via Bluesky.

If you liked this newsletter and want to support me, consider signing up for a paid subscription. You won’t get anything — yet — although it’s appreciated, and it’ll go some way to paying for the cymbalta I need to actually write this shit.

Next post, I swear, will be the one I’ve been writing for the past few weeks about how the Internet dies.

Cripes. On a friday night in, with a bottle of vino to take the edge off, this Gen-Xer's existential dread is reawakened. Thanks.

"While I’m not denying other generations had it rough — I wouldn’t have wanted to come of age during the Vietnam War, or the stagnation years of the 1970s — at least things eventually got better."

It didn't get better. Those of us who endured endless jobhunts for £1 p/h, yuppies, and AIDs, all under the threat of nuclear incineration, learned cynicism and to keep our eyes open.

We see you. We feel for you.

We don't know what to do either.

To get a good sense of this phenomenon, read the first part of The Executioner's Song. Life in the 1970s for a violent ex con was immeasurably better than it is now for a college-educated zoomer.